in my last blog post, i talked about how to write a simple shell script to orchestrate 2 common unix utility's - mkdir, and cd - to make a type of super utility, and called it cdnew. i got some interesting feedback.

some friends being supportive (and maybe slightly banterous), plus some kind strangers:

i also got a rather innocent, but actually very thought provoking comment:

initially, my reaction was something like: "huh... yeah... it is crazy. oh well".

but then i got to thinking "wait... why isn't there one? this seems so straightforward, could this really be an oversight? how hard could it be to write from scratch?"

a quick detour for some unix history

1969

original unix operating system (and kernel) created by K&R (Ken Thompson & Dennis Ritchie), written in PDP-7 assembly language, as a spin off of the eventually terminated multics operating system project at AT&T's Bell Labs

B programming language created by Ken.

1970

unix operating system ported to PDP-11 assembly language.

1972/1973

C programming language created by Dennis.

unix kernel (mostly) rewritten in C, some PDP-11 assembly still existed.

early 1980s

unix licensed out by AT&T. many "unix-like" OSes spawn (BSD, Xenix, etc)

AT&T settles second antitrust case with US govt, finally breaking up the bell telecom monopoly - which the US govt failed to do in the first antitrust case in 1956, which itself only resulted in a consent decree to allow competitors to license AT&T technology for nominal fees or even for free.

breaking up of AT&T meant the requirements of the consent decree were relieved entirely - AT&T now chooses to directly sell latest version of unix (system v) as a commercial product.

Richard Stallman begins GNU project at the MIT AI lab, a free open source software project aimed at providing a unix-like OS for free - later leaving the lab to continue the project and prevent the lab from interfering with its FOSS status

K&R receive turing award for their creation of unix

late 1980s

unix wars. POSIX standardisation by IEEE.

1990's

linux kernel developed & released by Linus Torvalds as FOSS, due to GNU project not having released an actual kernel. GNU/Linux composed of GNU's C compiler (gcc), C library (glibc), GNU's debugger (gdb), and some other bits; and the actual linux kernel.

apple acquires next, formalises xnu kernel.

now

you're probably reading this on a device running a unix-like operating system (macbook? iphone? android?)

syscalls

the premise is simple - i want to create a new directory (potentially an entire path structure), and subsequently change the working directory of the process running the command to said directory/path. how do we do that without just calling mkdir and cd? well, how do those utilities themselves work? turns out, under the hood (and i mean like wayyyy wayyyy wayyyy under the hood), they use something called syscalls.

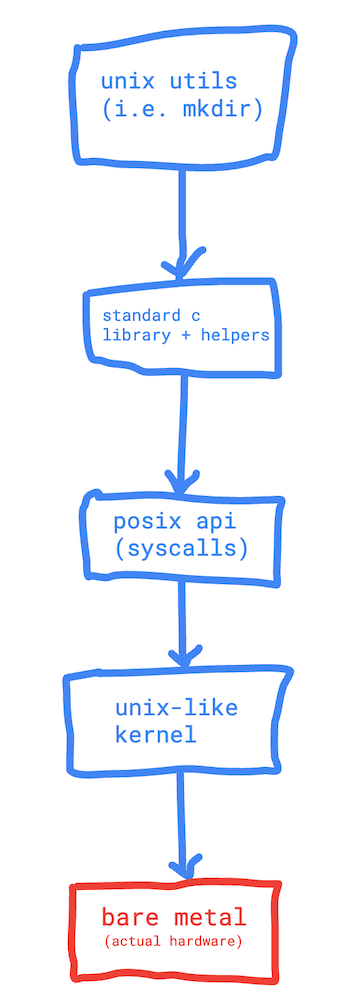

naively put, an operating system is split into user space and kernel space. in the unix kernel - and modern implementations like linux, and xnu (macOS) - there are uniform ways of exposing functionality to the operating system. for a program running in user space, to access these functionalities - like low level networking, modifying the filesystem, interfacing with the actual bare metal hardware, or whatever else - it must eventually use a system call to bridge the gap (so to speak) between user space and kernel space.

unix userland stack

when executing a utility in our shell, there is a "stack" of systems the call is being made through before it reaches the kernel. this is known as userland.

so clearly, when calling mkdir or cd, a c program must be running under the hood, through the wrapper layer, through the libc layer, and making a raw system call to the underlying kernel to do some work. to write cdnew without using mkdir or cd, all we'd need to do is figure out what those system calls are and use them.

fork and exec (and spoon, and maybe other cutlery)

given i'm running an arm64 macos system, i want to be able to figure out to write our cdnew program calling raw xnu syscalls. thankfully, xnu is FOSS, so we are able to see this documented very clearly here.

in that master list of system calls, we can see both mkdir and cd have their very own system calls named 136 AUE_MKDIR and 12 AUE_CHDIR respectively.

what the hell? is it really that simple? ok, let's write it.

#include <unistd.h>

int main ( int argc, char **argv ) {

syscall(136, argv[1], 0775);

syscall(12, argv[1]);

}

where argv[1] is a char* of a path structure like "path/to/new/directory" which we will pass as an argument to the compiled cdnew binary, 0775 is rwxrwxr-x for the correct directory permissions, and unistd.h (meaning unix standard) is a header file exposing the syscall c function to us in our cdnew program running in user space. our first syscall is to 136 which should be mkdir, and our second is to 12 which should be chdir or cd.

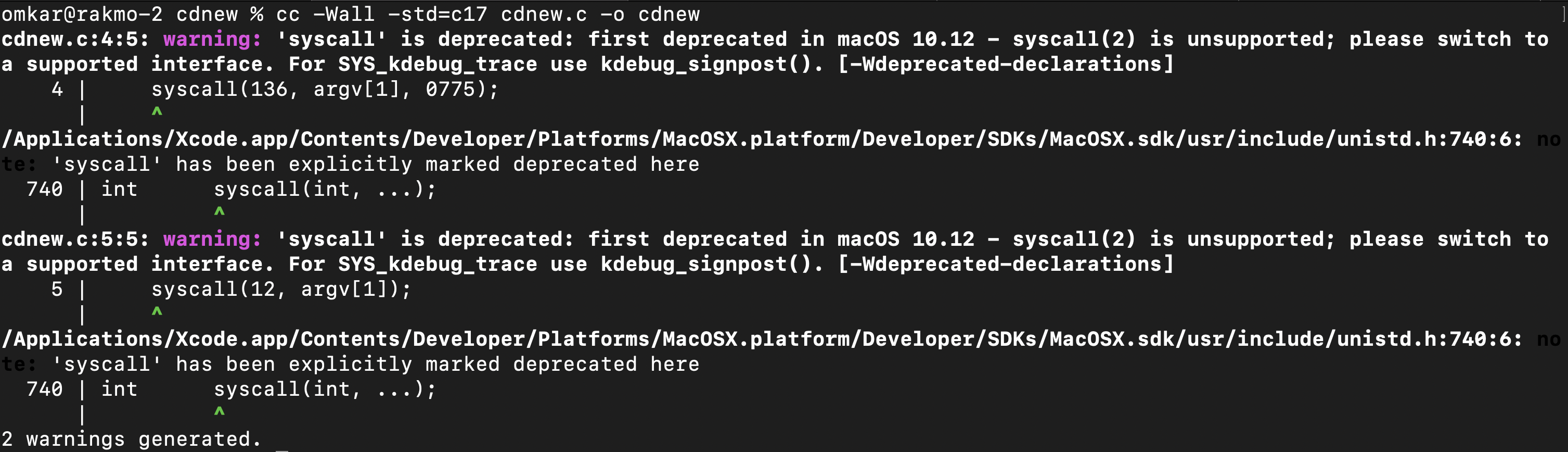

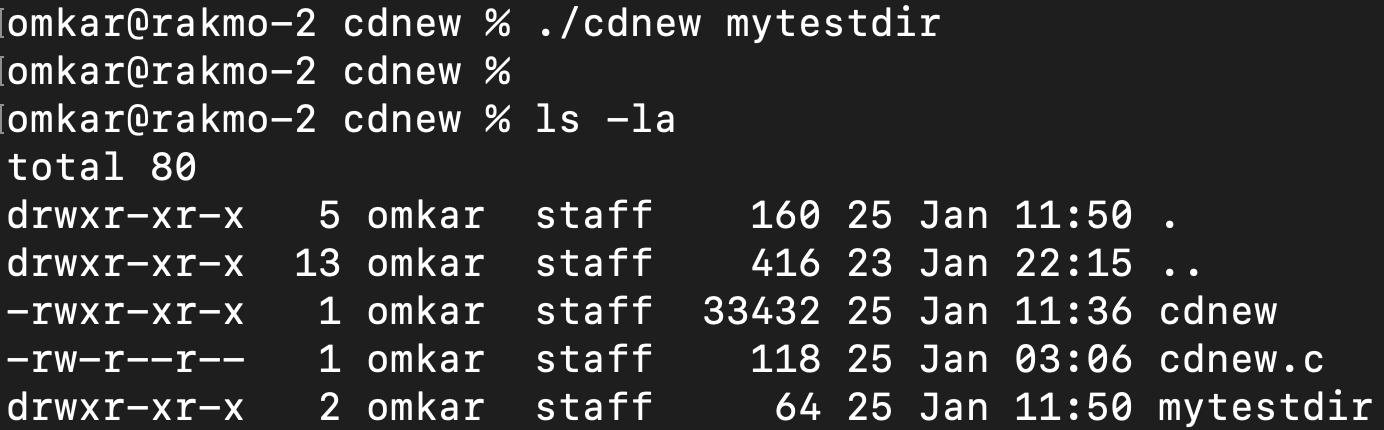

we should be able to compile this normally with cc (or gcc) like: cc -Wall -std=c17 cdnew.c -o cdnew and run the binary like ./cdnew mytestdir

let's do it

a bunch of warnings from apple telling us please for the love of god do not do this.

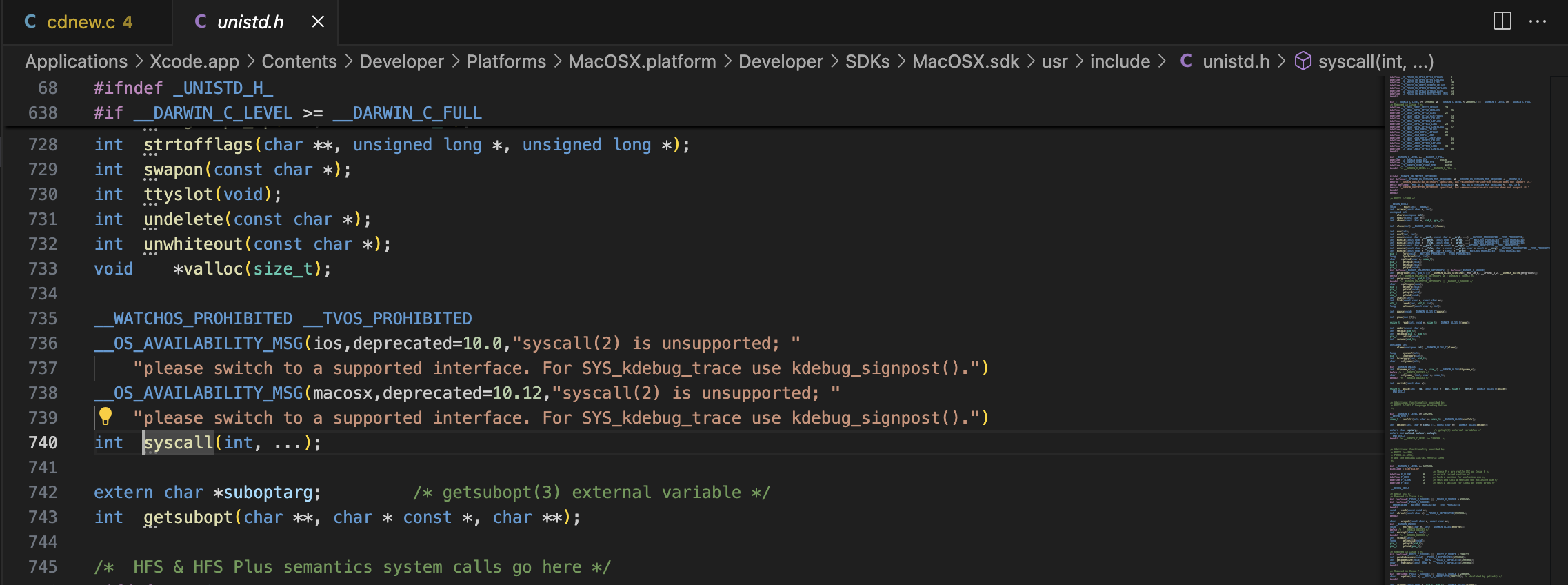

which makes sense, because if you step into the syscall header declaration in unistd.h, you can see a clear deprecation warning:

anyway, shut up tim apple, i'm doing it. let's just run the program and see what happens.

hrmph.. it didn't work. our current working directory has stayed the same. when we ls to read the contents, we do see the mytestdir directory was created implying the first syscall worked, but why didn't the second one work?

sometimes rules exist for a reason (lame)

the reality is that both syscall's did work, but unix-like operating systems have a user space technique called fork and exec. both fork and exec are themseleves system calls, and are used in conjunction with each other as a typical program pattern for all unix programs - including the shell itself! when we run our cdnew program, or any program for that matter, via a unix shell, the process forks itself (makes a replica of itself, but as a child process) and executes the program in that child process. the child process does not have access to any of the parents data or address space (except via open file descriptors), and simply runs the program before exiting and returning to the parent process.

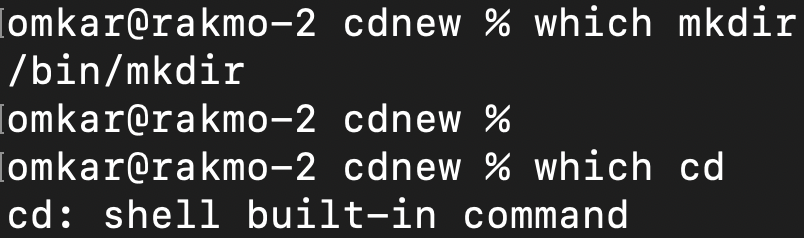

but then how does cd work? you might be wondering? it must use the chdir system call under the hood right? how does this not run into the same fork and exec problem that we're facing with cdnew? great questions. it turns out cd isn't actually a unix binary the way mkdir is (like we originally thought). it's actually what's called a shell builtin.

this means that a unix binary like mkdir is a compiled c program, like our cdnew program above, located in the /bin/ directory of our unix-like operating system, and this gets executed by the shell using the fork and exec pattern. cd is not a compiled program like mkdir, and instead is a function written straight into the shell program itself and is being executed natively as part of the shell process. no forking necessary (pardon my french).

takeaways

there are actually 2 reasons why cdnew can't be a unix utility: one is practical, and one is philosophical.

the practical we discussed already, i had an expectation that unix utilities are surjective onto the codomain of available syscalls, but a fundamental misunderstanding that cd runs as a unix utility like mkdir. cd is instead a shell builtin, and we can't replicate the functionality using the chdir system call because of the fork and exec pattern. even though, under the hood of the cd builtin, it likely is making use of the chdir system call, the shell makes it happen within the calling/parent process. this means cdnew can't really practically exist, and our original shell function from my last blog post is probably the the most reasonable way of solving this problem in user space.

the concept of isolation leads to the philosophical reason cdnew can't be a unix utility (see: unix philosophy). cdnew doesn't really adhere to unix philosophy: it doesn't do one single thing well, and it isn't designed to work with other programs (in fact, it's trying to combine 2 already existing programs). obviously a real implementation would be more sophisiticated, it would handle malformed inputs, it would have reasonable happy/unhappy return signals, and so on. but completeness aside, cdnew doesn't fit neatly into the character of a unix program. and that's ok. i am glad to have experimented with it anyway. try, fail, learn, repeat.